Three years ago, the National Archives and Records Administration unveiled a majestic eagle as its new logo. It has not taken long for the agency, like Icarus, to fly too close to the sun.

November 13, 2017

Three years ago, the National Archives and Records Administration unveiled a majestic eagle as its new logo. It has not taken long for the agency, like Icarus, to fly too close to the sun.

November 13, 2017

Three years ago, the National Archives and Records Administration unveiled a majestic eagle as its new logo. It has not taken long for the agency, like Icarus, to fly too close to the sun.

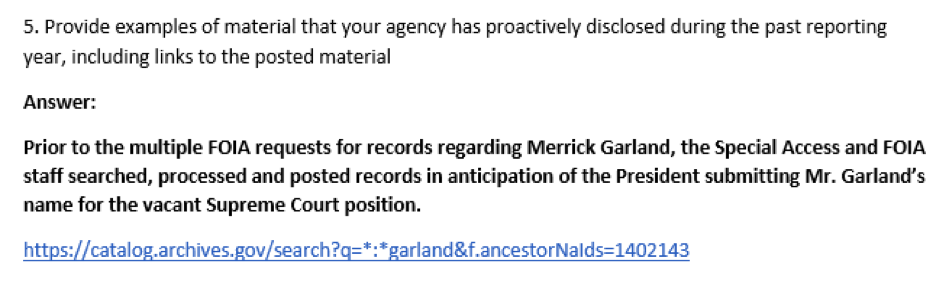

A few months after Donald Trump’s election dashed whatever hope Judge Merrick Garland still harbored to fill Antonin Scalia’s Supreme Court seat, the National Archives and Records Administration submitted a report to the Attorney General that took credit for a seemingly remarkable feat:

How in the world was NARA able to predict that President Obama would select Garland? Supreme Court expert Tom Goldstein, who handicapped the nominees for SCOTUSblog, never even listed Garland as a contender in his early assessments. Goldstein ultimately pegged Sri Srinivasan as the likely nominee, noting that Garland’s age was a significant factor against him. If NARA was not tipped off by the White House, the oracles at NARA ought to consider making road trips to Las Vegas. And how did NARA manage to process and post thousands of pages of records online in the short window between Scalia death’s and Garland’s nomination?

If you think the answers to the foregoing mystery are luck or foresight and elbow grease, you would be wrong. The agency neither expected Garland’s nomination nor posted Garland’s records online. It simply lied to the Attorney General.

The real story behind NARA’s Garland records is less dramatic. On March 25, 2016, nine days after Garland’s nomination, America Rising Squared (AR2) submitted three requests to NARA seeking access to records concerning Garland’s employment at the U.S. Department of Justice. The first of those FOIA requests sought the same records that NARA later claimed had been posted online before Garland’s nomination.

To its credit, NARA expedited AR2’s requests and — after reviewing the responsive documents for FOIA exemptions — the agency provided AR2 with access to tens of thousands of pages in May, July, and November 2016. With each release, NARA invited AR2 to visit its textual research room in College Park, Maryland to review the original documents. Per NARA’s protocol, AR2 was permitted to review only one box and one folder of documents at a time — all under the watchful eyes of archivists. Similarly, AR2 was permitted to copy documents one page at time only.

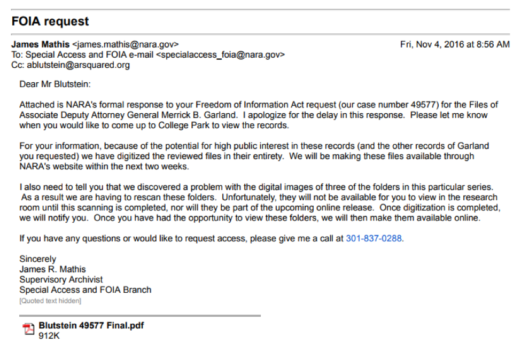

So when did NARA actually post the Garland records online, if not before Garland’s nomination and AR2’s requests? No need for super sleuthing. The concrete evidence appears in an email from NARA dated November 4, 2016, which states that all of the records requested by AR2 would be made “available through NARA’s website within the next two weeks.”

In sum, Garland probably sent out his robes for ironing in anticipation of returning to the D.C. Circuit before NARA posted its Garland records online.

NARA unquestionably deserves praise for its efforts in processing Garland’s records in response to AR2’s requests. But if NARA wishes to be “a strong, courageous advocate for transparent, participatory government that is accountable to its people,” as the Archivist stated three years ago, it should provide the public with accurate information about its own activities.