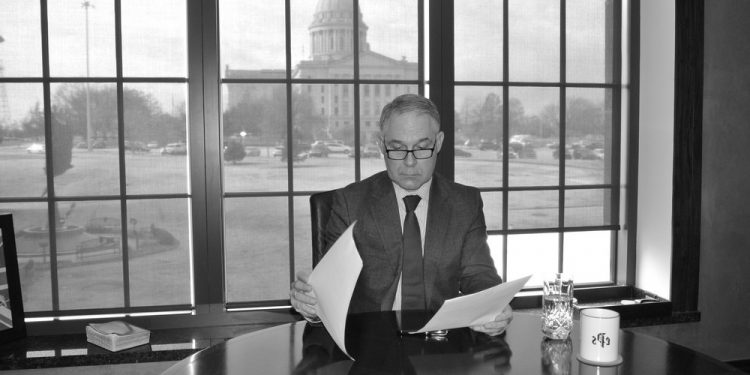

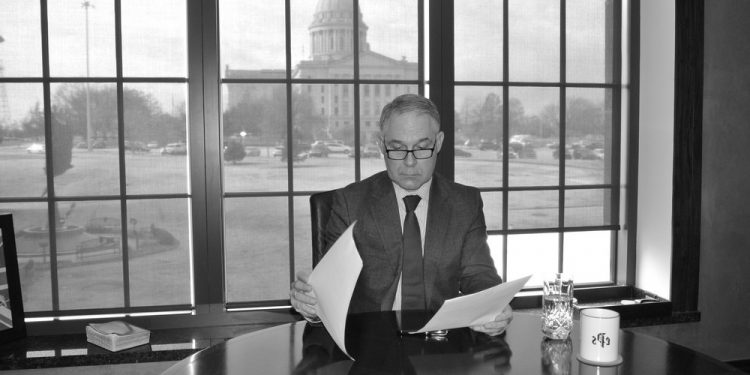

In his first interview since being sworn-in as EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt explains to Kimberly Strassel how he will work “cooperatively with the states to improve water and air quality”:

February 19, 2017

In his first interview since being sworn-in as EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt explains to Kimberly Strassel how he will work “cooperatively with the states to improve water and air quality”:

February 19, 2017

In his first interview since being sworn-in as EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt explains to Kimberly Strassel how he will work “cooperatively with the states to improve water and air quality”:

The New Administrator Plans To Follow His Statutory Mandate — Clean Air And Water — And To Respect States’ Rights.Republican presidents tend to nominate one of two types of administrator to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. The first is the centrist—think Christie Todd Whitman (2001-03)—who might be equally at home in a Democratic administration. The other is the fierce conservative—think Anne Gorsuch (1981-83)—who views the agency in a hostile light.

Scott Pruitt, whom the Senate confirmed Friday, 52-46, doesn’t fit either mold. His focus is neither expanding nor reducing regulation. “There is no reason why EPA’s role should ebb or flow based on a particular administration, or a particular administrator,” he says. “Agencies exist to administer the law. Congress passes statutes, and those statutes are very clear on the job EPA has to do. We’re going to do that job.” You might call him an EPA originalist.

Not that environmentalists and Democrats saw it that way. His was one of President Trump’s most contentious cabinet nominations. Opponents objected that as Oklahoma’s attorney general Mr. Pruitt had sued the EPA at least 14 times. Detractors labeled him a “climate denier” and an oil-and-gas shill, intent on gutting the agency and destroying the planet. For his confirmation hearing, Mr. Pruitt sat through six theatrical hours of questions and submitted more than 1,000 written responses.

When Mr. Pruitt sat down Thursday for his first interview since his November nomination, he spent most of the time waxing enthusiastic about all the good his agency can accomplish once he refocuses it on its statutorily defined mission: working cooperatively with the states to improve water and air quality.

“We’ve made extraordinary progress on the environment over the decades, and that’s something we should celebrate,” he says. “But there is real work to be done.” What kind of work? Hitting air-quality targets, for one: “Under current measurements, some 40% of the country is still in nonattainment.” There’s also toxic waste to clean up: “We’ve got 1,300 Superfund sites and some of them have been on the list for more than three decades.”

Such work is where Washington can make a real difference. “These are issues that go directly to the health of our citizens that should be the absolute focus of this agency,” Mr. Pruitt says. “This president is a fixer, he’s an action-oriented leader, and a refocused EPA is in a great position to get results.”

That, he adds, marks a change in direction from his predecessor at the EPA, Gina McCarthy. “This past administration didn’t bother with statutes,” he says. “They displaced Congress, disregarded the law, and in general said they would act in their own way. That now ends.”

Mr. Pruitt says he expects to quickly withdraw both the Clean Power Plan (President Obama’s premier climate regulation) and the 2015 Waters of the United States rule (which asserts EPA power over every creek, pond or prairie pothole with a “significant nexus” to a “navigable waterway”). “There’s a very simple reason why this needs to happen: Because the courts have seriously called into question the legality of those rules,” Mr. Pruitt says. He would know, since his state was a party to the lawsuits that led to both the Supreme Court’s stay of the Clean Power Plan and an appeals court’s hold on the water rule.

Will the EPA regulate carbon dioxide? Mr. Pruitt says he won’t prejudge the question. “There will be a rule-making process to withdraw those rules, and that will kick off a process,” he says. “And part of that process is a very careful review of a fundamental question: Does EPA even possess the tools, under the Clean Air Act, to address this? It’s a fair question to ask if we do, or whether there in fact needs to be a congressional response to the climate issue.” Some might remember that even President Obama believed the executive branch needed express congressional authorization to regulate CO 2 —that is, until Congress said “no” and Mr. Obama turbocharged the EPA.

Among Mr. Pruitt’s top priorities is improving America’s water infrastructure. “I’m going to be advancing this with the president, this idea that when we talk about investing in infrastructure, we need to look more broadly than bridges and roads,” he says. “Look at what happened in Flint,” the Michigan town where lead was found in the water supply. “Look at what is happening in California,” where the Oroville Dam’s failure endangers tens of thousands of homes.

Mr. Pruitt defies the stereotype of the fierce conservative who wants to destroy the agency he runs. Nonetheless, he is likely to encounter considerable hostility. The union that represents the EPA’s 15,000-strong bureaucracy urged its members to besiege their senators with calls this week asking them to reject Mr. Pruitt’s appointment. (The effort didn’t have much effect: The vote was nearly along party lines, with only two Democrats and one Republican breaking ranks.) These bureaucrats have the ability to sabotage his leadership. That’s what happened to Mrs. Gorsuch. She went to war with the bureaucracy, and the bureaucracy won.

Mr. Pruitt wants progress. “I am committed to the role of this agency,” he says. “The administration is committed to the role of this agency. There is so much to accomplish. So its important that the career staff here at the EPA know this isn’t a disregard for the agency, it’s a restoration of its priorities.”

He says EPA employees ought to be able to embrace his priorities: “Think about how tangible it would be to the citizens of Washington state to finally have the Hanford nuclear site cleaned up. Think about how tangible it would be to the citizens along the Hudson River, to fix that pollution. These are some of the most direct things we can do to benefit our environment. That ought to get people at the agency excited. It ought to get people in this country excited.”

Mr. Pruitt has read those laws his agency is charged with enforcing, and they guide another major change: a rebalancing of power between Washington and the states. “Every statute makes clear this is supposed to be a cooperative relationship,” he explains, “that Congress understood that a one-size-fits-all model doesn’t work for environmental regulation, and that the state departments of environmental quality have an enormous role to play.”

He faults President Obama’s EPA for its “attitude that the states are a vessel of federal will. They were aggressive about dictating to the states and displacing their authority and letting it be known they didn’t trust the states.” Mr. Pruitt has numbers to back up the claim: During the combined presidencies of George H.W. Bush,Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, the EPA imposed five federal air-quality implementation plans on states. Mr. Obama’s EPA imposed 56.

States’ rights were the motivating impulse behind Mr. Pruitt’s lawsuits against the Obama administration, and he has plenty of examples of the benefits of letting states take the lead on pressing environmental problems. He mentions the progress that a state coalition has made on improving the habitat of the lesser prairie chicken, a threatened species. States have also clubbed together to tackle water pollution in the Chesapeake Bay.

“There is this attitude that has grown of late that Oklahomans and Texans and Coloradans really don’t care about the air they breathe or the water they drink,” he says. “That’s just not the case.” As a demonstration of his commitment to the devolution of power, he pledges to vigorously defend the portion of the EPA’s annual $7 billion budget—roughly half—that goes to the states as funds and grants: “This is the front line of a lot of the work on air and water quality and infrastructure, and its very important that money continue.”

Mr. Pruitt argues that his renewed focus on statutes and federalism will help produce regulatory certainty, which will be good for business: “The greatest threat we’ve had to economic growth has been that those in industry don’t know what is expected of them. Rules come that are outside of statutes. Rules get changed midway. It creates vast uncertainty and paralysis, and re-establishing a vigorous commitment to rule of law is going to help a lot.”

His focus on jobs and the economy sets him apart from some past EPA administrators. “I reject this paradigm that says we can’t be both pro-environment and pro-energy,” he says several times during the interview. “We are blessed with great national resources, and we should be good stewards of those. But we’ve been the best in the world at showing you do that while also growing jobs and the economy. Too many people put on a jersey in this fight. I want to send the message that we can and will do both.”

Leading the EPA will be a role reversal for the former attorney general, in that it will place him on the receiving end of litigation. Lawsuits are proving to be the favorite weapon of the anti-Trump “resistance,” and environmental groups have declared their intention to bury Mr. Pruitt in court filings if he attempts to “roll back” their agenda. Yet he’s sanguine at the prospect. “Most lawsuits against the EPA historically have come either because of the agency’s lack of regard for a statute, or because the EPA failed in an obligation or deadline,” he says. “But we protect ourselves by hewing to the statutes. It will prove very difficult for environmental groups to sue on the grounds that they think one priority is more important than another—because that is something that really is at the discretion of agency.”

Speaking of lawsuits, Mr. Pruitt says he plans to end the practice known as “sue and settle.” That’s when a federal agency invites a lawsuit from an ideologically sympathetic group, with the intent to immediately settle. The goal is to hand the litigators a policy victory through the courts—thereby avoiding the rule-making process, transparency and public criticism. The Obama administration used lawsuits over carbon emissions as its pretext to create climate regulations.

“There is a time and place to sometimes resolve litigation,” Mr. Pruitt allows. “But don’t use the judicial process to bypass accountability.” Some conservatives have suggested the same tactic might be useful now that Republicans are in charge. “That’s not going to happen,” he insists. “Regulation through litigation is simply wrong.” Instead, Mr. Pruitt says, the EPA will return to a rule-making by the book. “We need to end this practice of issuing guidance, to get around the rule-making procedure. Or rushing things through, playing games on the timing.”

For similar reasons, Mr. Pruitt plans to overhaul the agency’s procedure for producing scientific studies and cost-benefit analyses. “The citizens just don’t trust that EPA is honest with these numbers,” he says. “Let’s get real, objective data, not just do modeling. Let’s vigorously publish and peer-review science. Let’s do honest cost-benefit work. We need to restore the trust.”